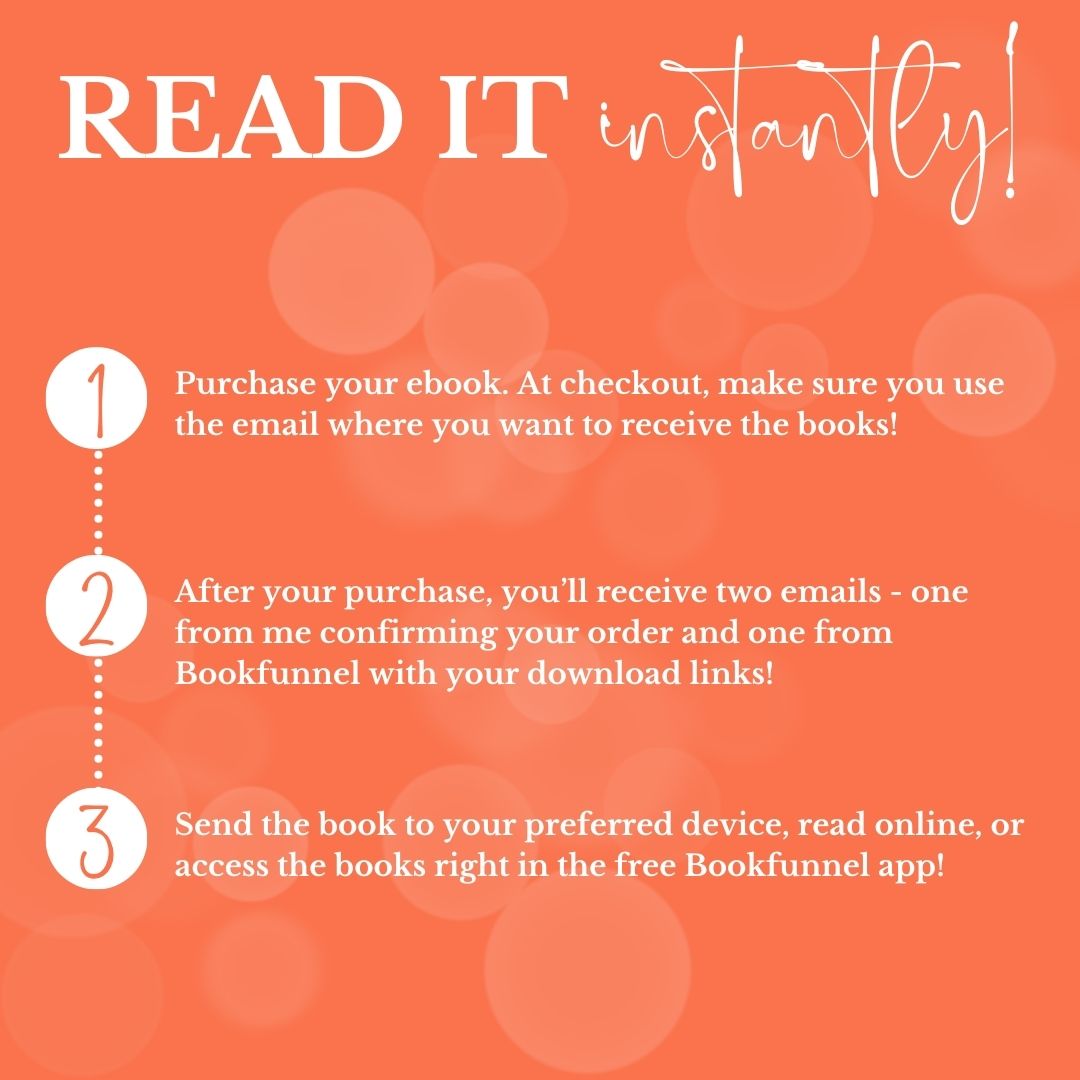

FAQ: How Do I Get & Read My E-Book?

- Purchase the e-book

- Receive a download link from Bookfunnel through the email address you used at checkout

- Follow the instructions provided at the link to download the book and sent it to your preferred device or read it in the free Bookfunnel app

Read A Sample

Chapter 1

“Do it,” Julie said, pulling me in front of her patio fire pit. “You’ll feel better.”

“You spent hours printing each one by hand on that ancient letterpress,” I told her. “I can’t burn them right in front of you.”

The box of elegant cards trembled in my hand. My closest friend grabbed a handful. She tore them in half and dropped them onto the flames.

“Do it,” she said again. “It will make me feel better.”

Julie’s husband Garrett poked my favorite rose-print bedsheets deeper into the fire. “Roast them, Marin. You know you want to.”

I know I should want to, I thought, wincing as a custom orchid illustration vanished in the flames. My eyes began to sting.

If they ask, I’ll say it’s because of the smoke, I told myself, swallowing hard. But I knew they wouldn’t ask.

“Don’t judge,” I said as I tucked one card into my purse.

I just wanted one. And only to keep until I didn’t want it anymore.

“I’m sorry you wasted all that time,” I told Julie, pitching the box into the fire.

One hundred wedding invitations spilled out onto the flames, flaring up fast. Like they wanted to burn.

Julie linked her arm through mine.

“I’m sorry you did, too,” she whispered, and I knew she wasn’t talking about invitations anymore.

Sparks snapped upward and disappeared into the heavy July night. Before I turned away, I saw the corner of one invitation curl in. I made myself look, but I was too late. Our names were already gone.

* * *

In the third week of my breakup—and subsequent breakdown—my mother staged an intervention. Not being an overly subtle woman, she didn’t lead me into a room filled with scented candles and my dearest friends. There was no mediator or moderator or whoever conducts those things. It was just my mom and my stepsister cornering me in the all-night diner beside my condo building to ask how long I planned to avoid my home.

“Not sure,” I said with a glibness that only my mother can inspire. “When I stop craving chili-cheese fries?”

My mother drew upon years of practice to expertly ignore this. “I noticed you’re still sleeping in your guest room.”

“You were at my place?” I directed this question at Nandila, my sister, and the only person left in my life who still had a key.

“We’re saving you from yourself. Get over it,” Nandi said, sticking her tongue out at me even as she abandoned the other side of the booth to slide in with me. But that was Nandi, thriving in her proprietary blend of loyalty and sass. We were sisters, despite our lack of shared blood and decade-plus age difference. The stepsister thing did not apply.

To be fair, the stepdaughter thing had never mattered, either. I saw my mom’s eyes get misty as this spirited younger daughter locked her lithe brown fingers into the elder’s wan, weary hand. But then her mission to rehabilitate the elder—to rehabilitate me—sharpened her focus.

“Well,” Mom said after clearing that rare sentimentality from her throat. “Are you going to spend the rest of your life hiding out in diners and catching three hours a night on the sofa bed? Or can we help you move back into your bedroom?”

“Sofa bed,” I told her. “My regular mattress is too soft anyway.”

“Don’t listen to her, she’s minimizing,” Nandi said. “And masking her emotions with sarcasm. Two classic Marin Beckett moves.”

“Did you switch your major from art to psychology?”

“Deflecting attention from yourself to someone else,” she replied with the smugness unique to bossy teenagers. “Another signature move.”

“The important thing, Marin, is to acknowledge your feelings,” my mom and her years as a professional therapist said. “If avoiding your condo will help you adjust, we’ll respect that. But you need to get some rest.”

I decided she was right, so in Week Four I swapped places with my sister. I left Alfred purring in my condo’s window seat; a dorm is no place for a cat.

“If you’re planning to work on your book, try Sunday and Friday. Most people on my floor will be hung over, so it won’t be as loud,” Nandi said. “Don’t take the back stairs, some dudes keep grilling on the landing. Hopefully you don’t mind the hot dog smells.”

I did my best, but after a week of frat boys puking in the halls and headboards knocking against the walls, I felt every one of my thirty-three years. Plus, my sister’s dorm was in the middle of campus. I could too easily bump into David, my ex-fiancé, who teaches literature at the university. Or into the co-ed I’d caught him bumping in our bed.

Five days later, at the start of Week Five, I smuggled Alfred into our new room at the Heart ’O Chicago Motel. I chose the Heart ’O Chicago for its vintage neon sign and reasonable weekly rate. The neon blinked in through the window all night, but I was up. It was good company.

Week Six. I was back on the sofa bed. Alfred was back in the window seat. And my parents, God bless them, took unprecedented steps to push me out of my self-pity, out of the country, and into a new frame of mind.

“Hello, Mariana,” my dad said over the phone later that week—he’s the only person outside the publishing world who always uses my full name. It was almost midnight, but I’m nocturnal even when not avoiding sleep, so he never hesitates to call me late.

For the sake of my digestive system, I had moved from the diner to the bar next door. While I guzzled coffee to keep myself awake, my brilliant-author father told me he was juxtaposing two obscure literary forms for the one essay he manages to publish each year, this one commissioned by The New Yorker. I did not mention that I was trying not to gag while thinking up euphemisms for various intimate acts. I’d been asked to write an article on sex and metaphor for the American Association of Romance Authors.

We spent a few minutes discussing his struggle to put words on paper—a struggle I had sadly come to know well in the weeks since becoming a cuckquean. If you’re wondering, that’s the female equivalent of a cuckold. And if you’re wondering how I know this, it’s from spending six years dating the literature expert who would eventually turn me into one.

“Can you visit tomorrow?” my dad finally said.

“Of course.” That he has health problems is an understatement, so I was instantly filled with concern. “Are you all right?”

“This is not about me. Your mother and I want to meet with you.”

I paused, certain I had misheard him. My mom had divorced my dad twenty years earlier. They hadn’t seen each other even one time since. “You and Mom want to meet with me together?”

“That’s the idea, yes.”

So many emotions rushed through me—joy, shock, maybe even dread—that I choked. My coffee cup was empty, so to soothe my throat, I had to chug the cold espresso I’d started carrying in one of the silver flasks David had bought for his groomsmen. This one was engraved with a Matthew Arnold quote, something about true friends beating down foes. Because a professor of Victorian poetry can’t just say thanks, man in plain English.

“Mariana?”

The apprehensive tremble in his voice triggered my own bout of nerves. I forced some cheer into my voice for his sake and told him I would love to come.

“Your mother said she’ll pick you up. Be here by six, please. And you could bring me some Black Forest cake from Cafe Selmarie.”

“Do you need anything else?”

“Some more of my pens, if it’s not too much trouble.”

Sure, sure, I thought, because remember how I said he has health problems? Of course I would get him the pens. And while I was out, I’d get myself a t-shirt with the word Enabler on the front.

My mother’s nose had already wrinkled at what she considered excessive middle-class privilege when I slid into her car the next afternoon.

“Does everyone in the plaza have a Starbucks addiction?” she said, watching four women clutching Ventis push strollers toward the fountain in my neighborhood of Lincoln Square. She sighed at their careful distribution of organic, DHA-supplemented milk. “Do they realize some kids don’t have milk at all?”

I expect my mother’s judgy brand of activism, so I didn’t respond. What I did not expect, however, was how her fingers knocked against the steering wheel throughout the drive from Chicago to my dad’s place in southern Wisconsin.

“Are you nervous about seeing Dad?” I finally asked at the outskirts of Wind Point.

Her hands fell flat.

“I was married to your father for seventeen years. I can spend an evening with him.” The words hadn’t left her mouth before the tapping resumed.

I lay my hand on my own anxious stomach. The butterflies I’d had all day were suddenly more like birds.

We pulled down my dad’s long drive to find him sitting on the patio with his back to us, watching the indigo swash of Lake Michigan bump against his yard. My mother gasped, maybe at the view but more likely at how the former love of her life had aged.

My attention snagged on his shabby little house. David had been planning to replace the cracked cedar shakes and repaint the porch before his fall semester began. Now I could either make the repairs myself or endure requesting the help of Ulrich Thompson, my dad’s landlord, who once told me while ogling my breasts that he not only reads my dirty novels but enjoys picturing me as the leading lady.

Dad’s thick white hair had blown over his forehead. Although it was mid-August, it was windy, and he was wearing one of his trademark cardigans. A brown fedora was perched on his knee. In his own way, he was bringing it, which did nothing to ease my nerves.

“Hi, Dad,” I said, draping my arm around his shoulders. I caught an atypical whiff of cologne when I kissed his cheek and the birds in my stomach beat their wings.

He patted my hand. “Hello, Petite.”

I should mention, I’m not that petite. I’m five-eight. But some nicknames refuse to die.

My dad was trying to be casual, but I felt him stiffen when Mom approached. She lingered behind the two of us, shifting her weight uncertainly from foot to foot.

I grabbed her hand.

“Well, here we are. Mom, you remember Dad,” I said, trying to lighten the mood as I prodded her toward the chair opposite his. “Dad, this is Mom.”

My parents stared at each other without speaking. Dad sat motionless but Mom teetered on the edge of her chair, her hands jittering awkwardly. I sighed when she began absently twisting her wedding ring.

I rested my hand on my dad’s shoulder again. “I brought your cake.”

He didn’t look at it.

“And a big bunch of pens,” I sang, waving around a Costco-sized box of Bics. That’s right, the simple black ballpoint is the writing utensil favored by renowned author John Robert Beckett. Reporters love this bit of trivia. One wrote an entire article comparing my dad’s literary style with this stark, no-frills pen. I’ve always wondered what that reporter might have written if I’d opened up the closets to reveal thousands of these literary metaphors hoarded within.

I left my parents staring at each other and went inside to cut the cake. While our coffee brewed, I poked around the house as I always did to make sure his panic disorder was still in check. Mantras? Displayed on every wall. Floors? Meticulously swept. Windows? Polished to perfection, bringing the calming waters of Lake Michigan as close to inside as they could get.

So, that’s some mischief managed, I said to myself, mustering a half-hearted laugh as I gathered up our cake.

My parents had moved from staring to chatting when I made it back outside. There were a few minutes of forks scraping against plates; these people are, after all, the ones who sired me and I’m not one to neglect a cake. But at last my dad cleared his throat.

“Mariana, we’re concerned for you.” His voice was strong and direct, and for some reason this made me slump into my chair.

“Really? I thought you guys wanted to get together after all these years to play cards. Maybe Old Maid?”

The look my parents exchanged was an exact replica of one I’d seen as a kid—the She-Inherited-That-Smart-Mouth-From-You smirk.

“It’s been more than a month and your mother tells me you can barely set foot in your own home. Did you really spend all of last week in a place called the Heart ’O Chicago Motel?”

I have to confess, I absolutely loved hearing my father, the literary legend, use the word ’O in something other than a reading of Keats.

“Mariana? Is this true?”

“Yes, I stayed there,” I finally said. “It was nice.”

Have you ever seen a Raul Fletcher International Book Prize winner roll their eyes? It’s awesome.

“Obviously our concern is not whether it was nice but why you felt the need to avoid your own home.”

“I’ll be honest. Walking in on an English major straddling my fiancé turned me off the place.”

“Marin…” My mom sighed, and my habit of firing back at her disappointment in me triggered what tumbled out next.

“Did I mention they were on top of Grandma’s quilt? The one she made me for my eleventh birthday, which makes the twenty-two-year-old quilt the exact same age as the girl David was with. It really killed the cozy vibe of home.”

I turned back to the lake so I wouldn’t see them trade She’s-Clearly-Overwrought nods. Also, I was a little embarrassed about the images I’d just unloaded on them, even though I knew that was silly. Twice a year, my mom and stepfather visit his native Zambia and sow condoms like seeds to fight HIV. I learned about the birds and the bees at age nine—at my dad’s own public reading of his memoir.

When I risked a look at them, their eyes were locked like they were deep in conversation. Seriously, twenty years without one bit of contact and these two people could still read each other’s thoughts? No wonder my dad has problems.

“We don’t blame you for avoiding the place,” Dad said. And then, as if they’d telepathically choreographed it, he and Mom leaned toward me and uttered the same words at once:

“We want to help you get away.”

“You do?”

“We do,” Mom said, her voice softer than I’d heard it in years.

Dad picked up his fedora and twirled it around his finger. I actually smiled; he’s so Frank Sinatra-cute sometimes. Then he said, “I’m selling the Seasalter house,” with a matter-of-fact look like this wasn’t the end of the world as we knew it.

I glanced from his face to my mom’s. They were both sober. I mean to say that they were both serious, but it’s also worth noting that they were not drunk. Because selling the Seasalter house was an idea they’d have to be drunk to consider.

It wasn’t just that it was the setting of Salt in the Sea, his bestselling memoir about his slide into mental illness—about how he’d clung to my mom and to me. It was that it was his childhood home, and mine. We hadn’t lived there since I was six years old, I could barely remember it, but I had been reading about it my entire life.

The house in Seasalter, the small coastal town in southeast England—a town with a name you could taste, could smell—that house was all that was left of my parents and me. It was us as a family, before the divorce, before panicked delusions and desperate tears that eventually forced us apart. It was the three of us sloshing through pebbled beaches, shrieking at lapping waves. My dad, so tall and tan, his hair white-blond in the sun. My mom freckling despite her huge straw hat, her own hair hanging down her back like a copper rope. It was what he had written about me, their Bell Petite, and the alchemy that had melded platinum and copper into a little girl with golden curls. These images, pieced together from my own memories and the pen of my father, were all I remembered of our life when it was only the three of us.

And the Seasalter house was proof it had been real.

“The London Literary Archive contacted me in May,” Dad said. “They’re planning a permanent exhibit on Salt in the Sea and want memorabilia. Papers and personal effects, things that belonged to us while we lived in Seasalter. It started me thinking I might unload the lot of it.”

“Dad, you’ve been planning this since May? Why didn’t you say anything?”

“You’ve been busy for the past few months, love,” he said gently.

Right. I had been busy. I had been trying on dresses and picking out flowers and enjoying all the cake tastings I could justify.

I winced at the idea, then winced again as I whispered my next words.

“What will you do without the income from the rent?” I hated to mention it in front of my mom, even if it was public knowledge. During their stormy divorce, his frazzled mental state had led him to donate all his money—including all future royalties from Salt in the Sea—to psychiatric research. He hadn’t published more than a handful of essays since my mother left. He barely got by.

“I’ll just visit the restroom,” Mom said tactfully. My dad’s eyes clung to her all the way through the front door before he turned back to me.

“Okay, Dad, what’s going on? Do you need money? Is there a problem I don’t know about?”

“Ulrich is selling this house.” My stomach flipped completely upside down, but before I could panic, he said, “If I can raise the money, he’ll sell it to me. It means I’ll never have to move.”

There was no way to argue with that. My dad’s tiny cottage on the shore of Lake Michigan was his only haven, the refuge in which he had sequestered himself to manage his complex OCD. I don’t know how renting affected my dad’s anxiety, but the idea that he might have to uproot himself from the one place he felt relatively safe was a constant source of stress for me.

“Values have climbed so in that part of England, you won’t believe the price the realtor quoted me for the cottage. The Seasalter property will bring more than enough for me to purchase this house, with money left over for necessities.” My dad looked at the ground. “What kind of fool throws away all his money? Without even bothering to buy a home first? I should have realized the burden would fall to you.”

“Dad, I don’t mind helping you,” I mumbled. “I love helping you.”

My father touched my cheek. “Then help me buy this place so I can stay.”

Behind us, the screen door banged shut. I turned to see my mother bent over the tangled hydrangeas blooming by the porch. Her long linen skirt caught on their branches. She pulled it free, laughing as a flurry of petals swirled to her feet. When I looked at my dad, the ache he was usually able to hide had bled across his face.

“Isobel,” he whispered as she disappeared around the side of the house. He squinted like the weak sun hurt his eyes, then he focused on me and his cheeks sagged.

“Mariana. My little bell. Help me let the Seasalter house go.”

And let go of the love for my mother that the house represented. I could read the words as clearly as if they were etched into the lines on his face. His eyes, blue like the water he needs to be near—blue like mine—were wet.

I took his hand in both my own. We sat in silence until my mom returned. And somehow he summoned the strength to his voice.

“The last regular tenants moved out in April. The Seasalter house has been a weekly rental all summer. I spoke with the property manager last week. The house is furnished and it’s been well-tended, but we need to clear out the attic. We moved out in such a hurry, I don’t remember what we left behind, but you know the book as well as anyone, Mariana. You can pull out some items worth giving to the Archive. See what, if anything, you want to keep.”

“You can get away for a few months,” my mother said. “And you can write as easily in Seasalter as you can here.”

I almost groaned. If that were the case, I wouldn’t churn out a word. When my own relationship fell apart, romance seemed to have been driven out of me.

“When is your next book due to your publisher?”

“March. It was supposed to be September, but they extended it. I earned some good grace when my Jane Eyre spin-off was optioned.”

“Rightly so. Not every novel gets made into a TV movie.” My dad is thrilled that I’m a writer. He doesn’t mind that my forte is torrid love.

My mom, however, is less enthused. “Which name do you use for the historical books again?”

“Mariana Rose. The contemporary novels are Beckett Bell.” Don’t worry, I almost told her. None of them can be traced back to you.

“It’s filming in England, right?” She pushed some enthusiasm into her voice. “Weren’t you invited to visit the set? Now you can go.”

“The set visit was scheduled for the week I called off the wedding. I was not in the mood for a meet-and-greet. I’m still not in the mood.”

“You can’t shut yourself away forever, Marin.”

“I’m not!”

“Skipping the set visit? That sounds like avoidance to me.”

“Back to our Seasalter idea.” My dad’s sharp tone silenced us both. “Ulrich is retiring next spring and wants to sell this house before then. But he’s agreed to give me time to get the money together. You can leave anytime. And you would have a few months in England to figure things out.”

“To figure things out or to sort through the house?”

“However you choose to see it.”

I picked up his hand again, focusing on the freckles scattered over his pale skin. “Dad. I don’t want to leave you alone.”

When he squeezed my fingers, his grip was firm, like he was trying to prove he wasn’t as frail as I feared.

“I have everything I need right here. What I want most is for you to be happy.”

“You can have your own adventure, Marin,” my mom said. “Anything could happen.”

I stared out at the lake once more. A late-summer firefly flickered near the shore.

“And I could see the Seasalter house,” I said, more to myself than anyone else.

When I looked back at my parents, they were gazing at each other with the same satisfied smile, like they already knew I had decided to go.

Sensitive Content

I try to depict my characters’ conflicts in the most honest way possible. But I also appreciate that every reader has the right to choose what information they want to allow into their brain. I want you to enjoy my books, and I would never want to upset you with tough aspects of the plot.

Below, I’ve included information about sensitive plot points, should you want to know more before reading.

Please be advised, these are spoilers about things that will happen to characters or have happened in a character's past.

If you want to know more, please scroll down. If you prefer not to know, please close this tab before scrolling down to read.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

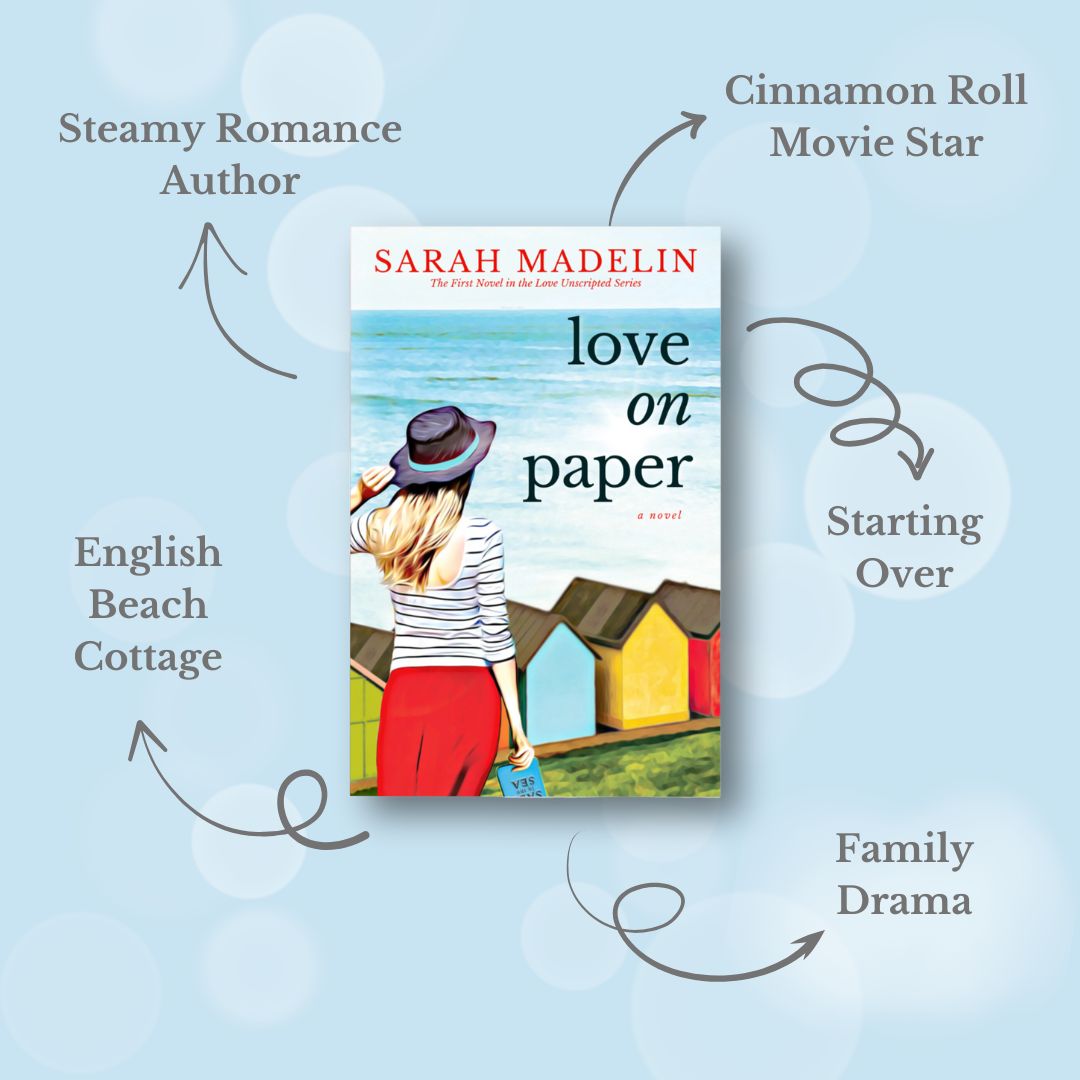

Love on Paper contains mild language and sensual content, features depictions of mental illness and serious medical injury, and references a prior incident of infidelity.